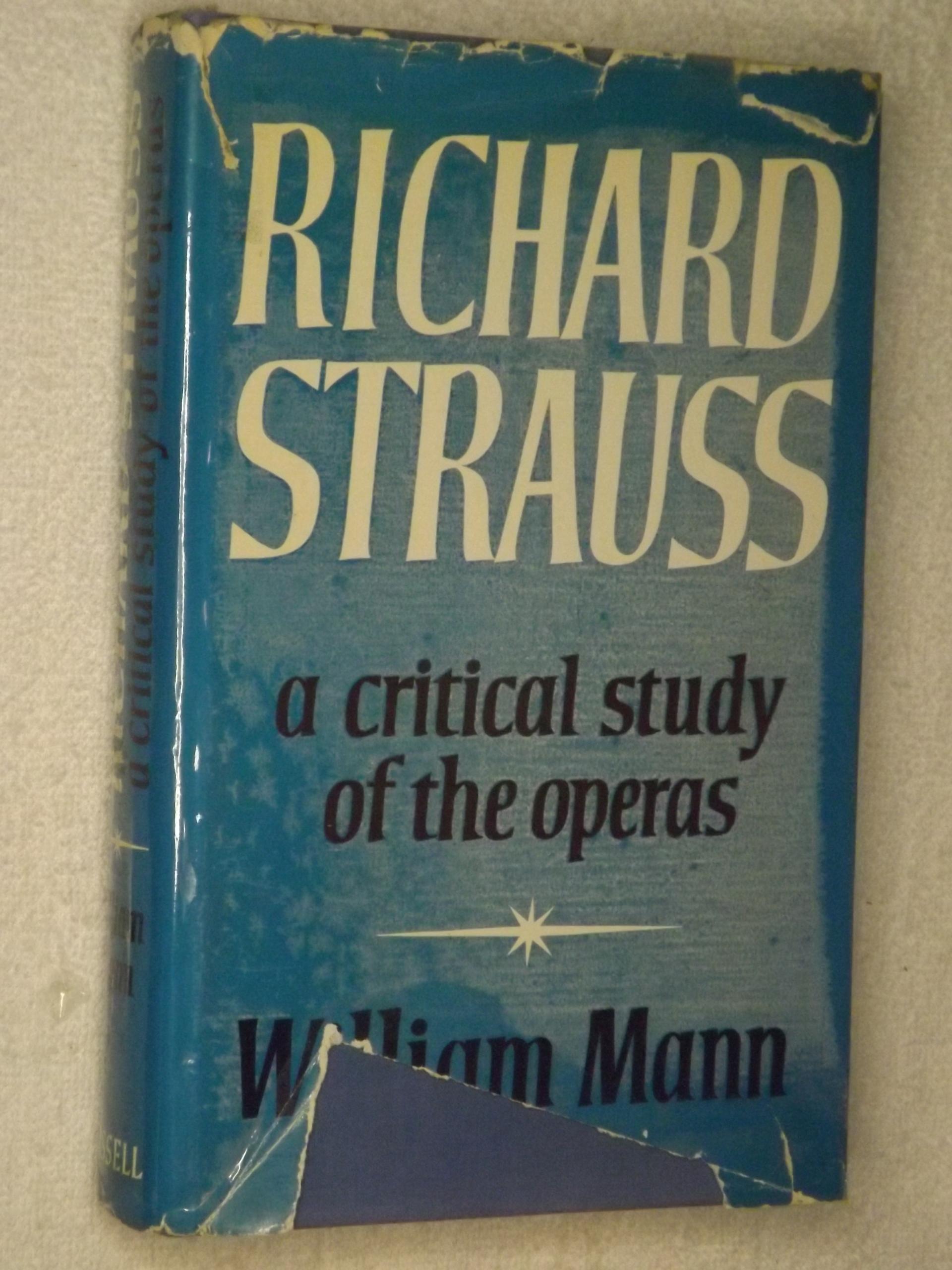

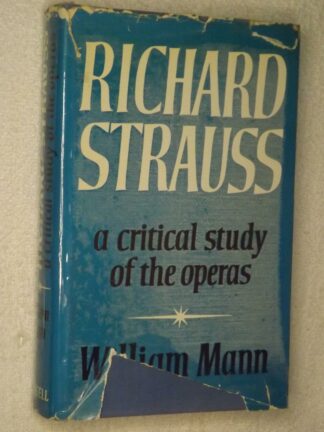

Beskrivelse

In his Preface to this volume, William Mann expresses the hope that his approach to the Strauss operas “might be half as valuable” as that of Ernest Newman’s masterpiece THE WAGNER OPERAS (a/k/a WAGNER NIGHTS). He need not have been so modest. Of course, he was tackling a subject far more controversial than the established merit of Wagner’s works. Strauss’s music was controversial for different and opposite reasons throughout his creative life – and long after. Regardless of ultimate “merit,” some of those reasons are not far to seek. Strauss hit his creative stride toward the end of the Romantic era – an era in which musical “progress” was assumed to be a discernible “straight line” on the way to some ideal or ultimate development of expression. At the time, this implied that the Beethovenian way was the ultimate measure of all things musical, and of course that the Ninth Symphony and the Late Quartets were the high point reached by all music, thus far. (Perception of the ultimate greatness of Bach and Mozart had yet to be anywhere near as established as it became in the following century – even considering the early efforts of Mendelssohn as to Bach.) This all meant that a composer had the duty to not only traffic in conscious profundity, but to “pick up where Beethoven left off.” In their different ways, Schubert, Schumann, Brahms, Liszt, Wagner, Bruckner, and Mahler all took this as Gospel. While he never denied the greatness of Beethoven, Strauss never accepted this whole complex of beliefs – which, for the sake of convenience, I will call GOSPEL # 1. From the very beginning, he responded to Mozart’s peculiar mixture of subjectivity and objectivity, while furthering Wagner’s leitmotif technique, and, in line with his own natural temperament, made those two sources of inspiration his own. (When a Nazi questionnaire arrived on Strauss’s desk, asking for the names of two composers who could “vouch” for his creative ability, he puckishly and rightly filled in the blanks with “Mozart” and “Wagner.”) With the advent of atonality (Schoenberg) and anti-Wagnerian “New Objectivity” (Stravinsky) after 1910, Strauss kept going on his own path. Even at the height of his influence and notoriety, while working on ELEKTRA in 1907, he denied in writing that there could be any such thing as a “progressive party” in music. To him, the question was irrelevant. However, to the avant garde and overall musical criticism which developed after the cultural PRAXIS of World War I, that question was anything BUT irrelevant. Indeed, atonality – or at the very least, radical harmonic innovation or “progress” – was as equally unquestioned a Gospel as the Beethovenian ideal had been, earlier. (Call it GOSPEL # 2.) Strauss, remaining true to himself, fell afoul of both Gospels.